Exiting through the lobby, you couldn’t miss a familiar, heartening post-screening buzz: sounds of laughter and exasperation; hesitant, hazardous attempts at analysis; confused variations on “What was that all about?” We could have just seen “Eraserhead” or “Blue Velvet,” or stumbled out of “Mulholland Drive,” as some friends and I did, not too far away, more than two decades earlier.

Therefore, perhaps directing the spirit of Betty (Watts) and Rita (Laura Elena Harring), the film’s amateur-sleuth lead characters, my pal and I started our nighttime trip. Visiting throughout the day might have made much more sense, yet making sense really felt antithetical to the spirit of “Mulholland Drive,” and I had no passion in ruining its spell. I just intended to remain in its atmosphere a while much longer, to hold at Peter Deming’s seedily shiny images and Angelo Badalamenti’s mournful caress of a rating. I questioned what we might see: a black limo, winding its means towards a roadside blaze? A woman tottering downhill in a daze, the glittering magic-carpet stretch of Hollywood sloping off into the distance? We saw absolutely nothing of the type, certainly; the real Mulholland Drive appeared as hesitant to surrender its keys as Lynch’s movie was. All I bear in mind seeing, by the light of the car’s high beams, was a grocery-store purchasing cart deserted on the side of the roadway. I chose– with a little overreach, undoubtedly– that this was a remarkably Lynchian strangeness: something commonplace that, by appearing where it really did not belong, came to be ineluctably sinister.

The weekend after Lynch died, “Inland Realm” took place to be showing in an American Cinematheque retrospective, and the event came to be a kind of impromptu memorial. The testing went to the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood, plain steps away from the place where Dern’s Nikki startled, fell, and vomited all that blood, and the area was packed with Lynch enthusiasts. Prior to the main feature, the Cinematheque screened a short passage from a video interview, in which the director spoke about his particular love for Los Angeles:.

For me, it was “Mulholland Drive,” a motion picture that might have been too much for television (it was notoriously restored from the damages of a declined ABC pilot), yet proved to be the best kind of excessive for movie theater. This was the movie that lastly made a four-star follower out of Roger Ebert, until then a longtime important holdout on Lynch’s work. (” There is something inside of me that withstands the films of David Lynch,” started Ebert’s pan of the director’s 1990 movie, “Wild in mind.”) In the years because, “Mulholland Drive” has actually become Lynch’s agreement work of art; it landed at No. 8 in the 2022 View & Sound doubters’ survey of the greatest films of perpetuity. I’m supportive to the idea, as some have whined, that all this canonization is a little bit early, which the large seductiveness of “Mulholland Drive” has made it a little as well hip and simple to enjoy: the most standard bitch of Surrealist classics. I’ve never come close to falling out of love with it. To do so would certainly really feel a little like falling out of love with Los Angeles itself.

For weeks, Lynch’s movie had actually haunted me like absolutely nothing else. It was amusing and dark and sexy and intoxicating– a desire that followed me out of the theater and into my waking reality, and a photo that eliminated, and after that thrillingly restored, my understanding of what movies might do. For a nineteen-year-old blossoming cinephile whose idea of nonlinear storytelling had been shaped by Quentin Tarantino, it was astonishing to see a filmmaker so well-versed in the verse of the illogical. I was least ready of all for just how ruined “Mulholland Drive” would leave me: how could a movie so arrestingly unusual, with so many layers of deadpan absurdity and film-noir pastiche, likewise be tender and moving past words?

Somewhere else, Lynch was an insistent creature of behavior, and his routines– constantly putting on top-buttoned white shirts, permanently espousing the virtues of Transcendental Reflection– typically became the stuff of local legend. Later in his career, Lynch captivated his fans– and doubtless made some brand-new ones– with a series of day-to-day weather records, delivered from his perch in the Hollywood Hills. It never ever would have taken place to Lynch that there was any kind of opposition to begin with.

Lynch stopped doing weather forecast in 2022. A long-lasting smoker, he announced in August that he was suffering from emphysema so severe that he had been properly housebound because the COVID-19 pandemic. I can’t help but wonder what meteorological projections he may have supplied this January, because of the devastating wildfires that have devastated Los Angeles. A Target date report priced estimate anonymous sources declaring that of the fires, the Sunset Fire, forced Lynch to transfer from his home, and that, after the emptying, the director’s perilous health had taken a turn for the worse. (No cause of death was given.).

Lynch’s movies are frequently called unnerving and unique, a totally precise assessment that doesn’t completely catch the terrible chaos they can create on a newcomer’s expectations. I can only envision the preliminary impact of “Eraserhead,” Lynch’s imaginary début function, when it initially arised, in 1977, and came to be a midnight-movie experience. Yet I still bear in mind seeing it for the first time and believing that nothing I ‘d review it, in squeamish preparation, might have possibly blunted the pustular splendor of its photos, the otherworldly drone of its audio style, or its air of lysergic rot. “Eraserhead” was a motion picture that made you really feel as though you ‘d absolutely seen everything, yet Lynch had far more to show us. His style for the monstrous discovered an affecting, all of a sudden timeless structure in “The Elephant Guy” (1980 ), which made him the initial of 3 richly was worthy of, unsurprisingly unsuccessful Oscar elections for Finest Director. Next off came the commercial and essential catastrophe of “Dune” (1984 ), an uncommon venture right into studio filmmaking that Lynch inevitably disavowed; already, however, the unconfined intricacy and imagination of his aesthetic style might rarely be ascribed to any various other filmmaker.

Even amongst Lynch’s more thoughtful admirers, the need to emphatically pin him down continues apace. Debates still surge about the accurate proportion of genuineness to irony in the supervisor’s job– a discussion that, for me, ultimately says much less about Lynch than it does regarding the limitations of vital language, especially when such language is related to a musician whose work is this unfiltered and second-nature. However, I ‘d venture that there is both sincerity and irony aplenty in Lynch, and both aren’t always in tension; each one illuminates and nourishes the other. Think about them as sweatily companionable bedfellows– or, if you favor, transmigratory hearts.

I like the light there. And I like the feeling of it.

I’m constantly saying, when you exist in L.A., on some nights in.

summer season, perhaps the spring, this night jasmine odor comes, and.

often there’s a wind, and you can feel the golden age of Hollywood.

airborne, and it’s quite wonderful. And there allows workshops, big.

sound stages. I love these large sound phases, manufacturing facilities for making.

movie theater. So there’s– and then there’s the star system, and all this.

taking place. It’s all sort of part of this dream. There’s a lot wrong.

with it, but that component is a big attraction to people.

Lynch’s love for Los Angeles, and the unmatched, unfakeable truth of his visibility around the city, offered the lie to that fee. (It was one of the few times that he came even close to offering a rationale for his job.).

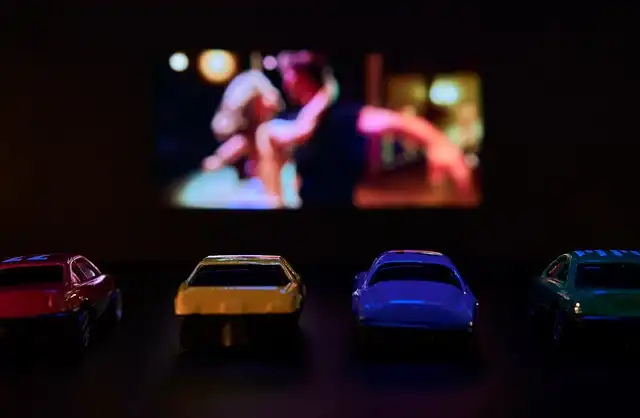

“Inland Realm” was, among other points, a furiously comprehensive exploration of that “a great deal wrong with it.” When the flick was initial launched, it was appropriately welcomed as a darker, uglier, even more violently destabilizing buddy item to “Mulholland Drive”– another dreamlike taking down of the dream manufacturing facility, just this moment, the desire had been completely shorn of its seductive verve. For 3 hours, Nikki, played by Dern with an usually terrifying majesty, browsed a shifting maze of chambers and antechambers, run-down homes and cavernous sound phases, losing and building up identifications at every turn. She was stalked and menaced, sank in identities however robbed of selfhood, and– just to highlight the motion picture’s view of Hollywood as a pimp’s game– thrust into a roomful of leering, dancing sex workers. “Inland Realm” was a prediction and a disaster: it was Lynch’s very first (and last) feature movie fired on digital video clip, a medium that, in its second hand and convenience of use, motivated his will certainly to experiment. It additionally seemed to catch, in the grubbiness of its textures, the vibe of a Hollywood degrading and swiftly fading past acknowledgment. The film made no sense; it made all the feeling worldwide.

One night in January, 2002, throughout the first theatrical run of David Lynch’s “Mulholland Drive,” a good friend and I, pupils at the University of Southern California, increased towards the Hollywood Hills to choose the roadway itself. Mulholland Drive runs a curvy twenty-one miles lengthwise, and we didn’t drive almost the whole means. We went into off the 101 Freeway, just north of the Hollywood Bowl, and headed slowly west, relying greatly on our fronts lights to find our way through the darkness. From time to time, we pulled over to search for a great sight, however generally just to rest there in the dark, saturate up the silence, and chat a little bit much more about the most remarkable movie we had actually seen in ages– a confounding and gorgeous thriller concerning an auto crash, a bubbly blonde starlet, a dark-eyed amnesiac, a sulky director, a shitty espresso, a po-faced cowboy, a hobo behind a dumpster, Roy Orbison, Rita Hayworth, “Character,” “Vertigo,” and more.

And if it makes no sense now that David Lynch is gone, there is consolation in recognizing that his existence among us was, to start with, one of the most illogical and unjust of presents. Certainly, there was relief in the event that Saturday night, where the respect of diehard Lynch obsessives seemed to combine, excitingly, with a novice’s feeling of bafflement and discovery. Leaving with the entrance hall, you couldn’t miss a familiar, heartening post-screening buzz: audios of giggling and exasperation; reluctant, hazardous attempts at evaluation; puzzled variations on “What was that everything about?” We can have just seen “Eraserhead” or “Blue Velvet,” or stumbled out of “Mulholland Drive,” as some pals and I did, not also far away, more than two decades previously. And after that we did what we did back then– roamed out, lost in thought and in movie theater, right into the dark shimmer of another L.A. evening. ♦.

In the days and weeks considering that Lynch’s death, at the age of seventy-eight, I have actually found myself assuming a great deal about the Los Angeles that he left behind. He was, to ensure, a pan-American artist, with a perceptiveness soaked in many a regional cauldron. Missoula, Montana, where he was born, bequeathed him a down-to-earth Eagle Precursor congeniality, all nasal delivery and gee-whiz excitement. He invested a lot of his childhood years in Spokane, Washington, a period that would certainly be enshrined in the lushly menacing Pacific Northwest landscapes of “Double Peaks.” He studied paint at the Pennsylvania Academy of Penalty Arts, in Philly, a city that he later explained, in interviews, as a location of unique foulness: “I saw awful things, dreadful, dreadful things while I lived there,” he told the Philly Inquirer, in 1986. “It was truly motivating.”

Prior to his death, it was possible to state, or a minimum of hope, that every generation would obtain the Lynch masterwork it should have. For his earliest admirers, it was definitely “Blue Velour”; for a much more recent wave of converts, it might have been “Twin Peaks: The Return” (2017 ), the magnificently uncompromised 3rd season of his site 1990-91 television series, “Double Peaks.” Still others would certainly make the instance– and I wouldn’t disagree– for “Double Peaks: Fire Walk with Me” (1992 ), a terrible feature-length spinoff that, obtained at the time with refuse and confusion, has actually because been redeemed as one of Lynch’s supreme achievements.

In the years that complied with, I ventured out trying to find even more “Mulholland Drive” hot spots. The farthest-flung of these was in Paris, where, in 2013, some good friends and I half-heartedly tried to enter Club Silencio, a club designed on one of the movie’s most impressive series. A lot of my adventures were closer to home. A year approximately afterwards Mulholland drive, I end up outside a Silver Lake apartment complex, charming in mock-Tudor brown and beige, that had actually in some way led Lynch to believe, Ah, yes, what a perfect area to uncover a corpse. If I had actually ventured about fifteen miles south, to Gardena, I can have appreciated a mug of coffee at Caesar’s Dining establishment– a currently shuttered diner that, thanks to “Mulholland Drive,” will live forever as Winkie’s on Sundown Blvd. Here, Lynch advised us that the most chilling nightmares unfold in wide daytime.

“Mulholland Drive” was the 2nd film in Lynch’s unofficial L.A. trilogy; the other two left their own marks on the landscape. Already, I can not walk down Hollywood Boulevard without briefly reflecting back on “Inland Realm,” in which a tormented movie actress, Nikki Poise (Laura Dern), is gutted with a screwdriver and throws up blood throughout the Stroll of Fame: “You dyin’, girl,” a homeless observer mutters. One more Lynch landmark was his three-house substance in the Hollywood Hills, component of which ended up being an embeded in “Lost Highway”– transformed, in what seemed like an act of virtually confessional intimacy, into a distended maze of residential horror, where also a darkened corridor can open a website to the unknown. To speculate concerning what that unidentified could be component of the enjoyable; it might additionally be close to the factor in a flick that never ever when departs the uproar of Lynch’s subconscious.

One night in January, 2002, during the initial staged run of David Lynch’s “Mulholland Drive,” a pal and I, pupils at the College of Southern The golden state, drove up toward the Hollywood Hills to look for out the road itself. We saw absolutely nothing of the type, of program; the actual Mulholland Drive appeared as unwilling to surrender its secrets as Lynch’s movie was. A year or so after that Mulholland drive, I wound up outside a Silver Lake apartment complex, lovely in mock-Tudor brownish and beige, that had in some way led Lynch to think, Ah, yes, what an excellent place to find a corpse. In the years since, “Mulholland Drive” has actually come to be Lynch’s agreement masterpiece; it landed at No. 8 in the 2022 View & Noise movie critics’ survey of the greatest films of all time.” Mulholland Drive” was the 2nd movie in Lynch’s unofficial L.A. trilogy; the various other 2 left their own marks on the landscape.

Lynch relocated to Los Angeles in the very early nineteen-seventies to examine at the American Film Institute; there, he started working with “Eraserhead,” much of which was fired on A.F.I.-owned places. His later films, such as “Lost Highway” (1997) and “Mulholland Drive,” would expose more of the city’s seamy appeal, finding threat in the sunshine and roaming down treacherous roads to no place. His movies pleased in collapsing the city’s past and its existing with each other, in finding building and cultural remnants of an older Los Angeles embeded among the city’s newer façades. It’s considerable, I assume, that all three of Lynch’s L.A.-set films are so rooted in convulsive games of identification: think of Fred the saxophonist (Bill Pullman) changing inexplicably into Pete the grease monkey (Balthazar Getty) in “Lost Highway,” or Laura Dern shape-shifting at will certainly in every other scene of “Inland Realm” (2006 ). It’s as if Lynch were saying on not just the integral plasticity of the motion-picture tool but additionally on a city understood for its limitless self-reinvention– and commonly derided, wrongly, as a cesspool of inauthenticity.

For a few delirious months, “Mulholland Drive” came to be an obsession, the dream film of my dreams, even a precocious early statement of vital identification. At U.S.C., where relatively every movie student had a “Shawshank Redemption” poster on his dorm-room wall surface, taping up a stunning Italian one-sheet of “Mulholland Drive” really felt like a peculiarly rebellious factor of satisfaction. I came to be convinced– and then remain convinced– that Naomi Watts, the film’s incandescent star, had actually given one of the best performances of the still young twenty-first century.

Lynch attempted us to watch, through our fingers, as an uncomfortably off-kilter funny of sectarian mores became significantly subsumed in an erotic miasma of fairy-tale fear. The movie is built around an Oedipal triangle whose transgressive power hasn’t dissipated in the tiniest, relaxing, as it does, on the unsinkable foundations of its stars: a boyishly corruptible Kyle MacLachlan, a bewitchingly susceptible Isabella Rossellini, and a primally distressing Dennis Hopper. What lingers simply as persistently is a particular trickiness of intent– a feeling that Lynch himself, so aware of the facility, cooperative play of light and darkness in human nature, was material to sweep eternally, and with a mosquito’s fickle inquisitiveness, in between 2 moral poles.

1 Lynch2 Mulholland Drive runs

3 Southern California

4 University of Southern

« Trump disbands presidential committee on the arts and the humanitiesFKA Twigs Leaves It All on the Dance Floor »